A letter from the Munich Security Conference

From crisis buying to permanent capacity, rearmament now sees warfare challenge welfare.

Europe’s fiscal test

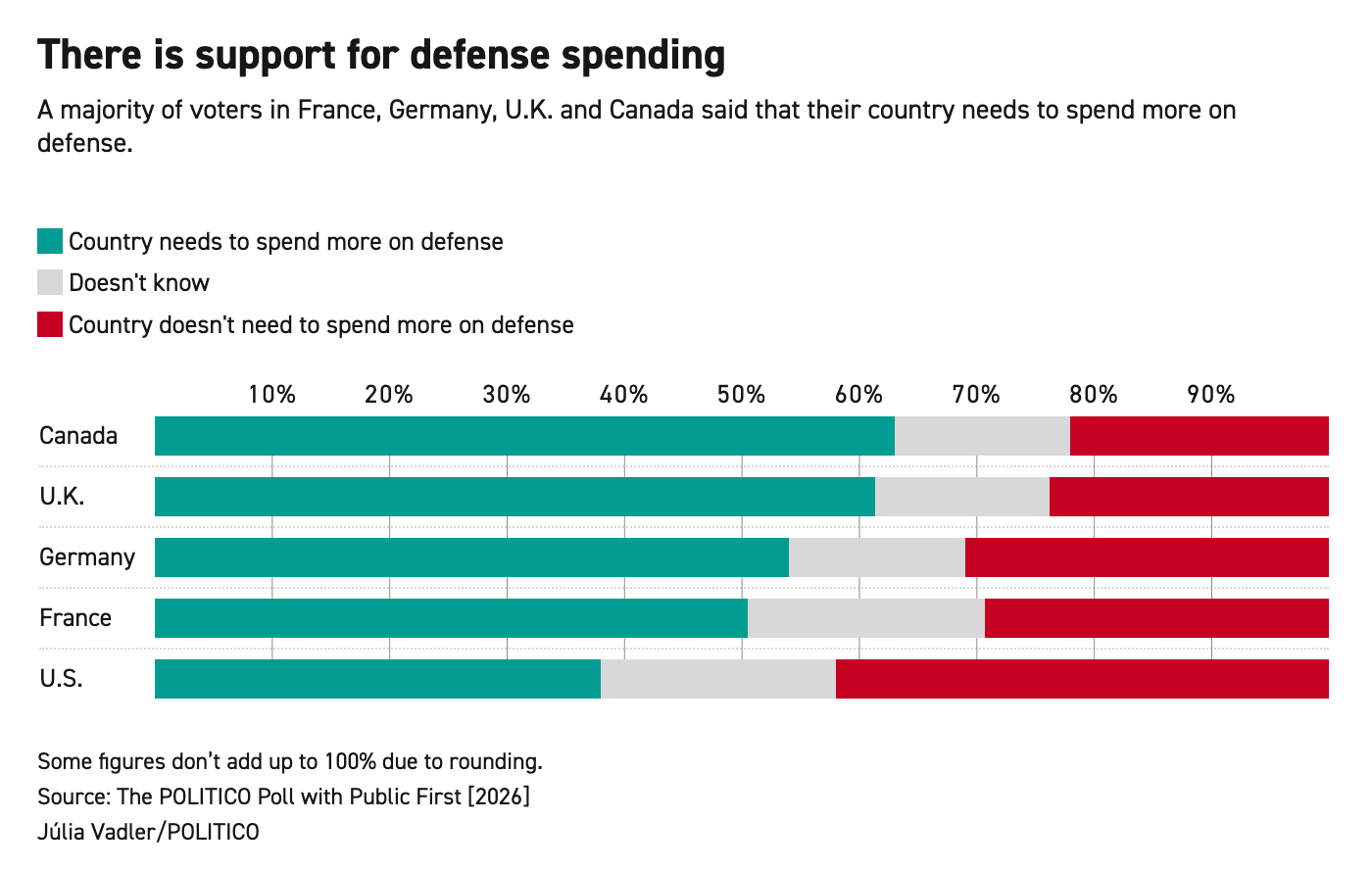

European voters say they support higher defense spending. But when asked whether they would accept higher taxes or cuts to welfare to fund it, approval falls from 40% to 28% in France and from 37% to 24% in Germany. That gap is Europe’s real defense problem.

The political ceiling on defense spending has collapsed. Germany is committing hundreds of millions to startups, procurement laws are being rewritten, and factories are expanding. Yet rearmament is entering its harder phase.

I attended the Munich Security Conference this year with that tension in mind: welfare vs. warfare.

The tone shifted, but expectations haven’t

Last year in Munich, US Vice President JD Vance delivered a blunt message that Europe’s vulnerabilities were internal as well as external, and that American support would not be unconditional. The speech was widely read as a warning that political alignment and defense spending were now intertwined.

This year, Secretary of State Marco Rubio struck a more conventional tone, emphasizing alliance durability and shared strategic interests. While the rhetoric softened, the expectation did not: Europe must assume greater responsibility for its own security.

But will voters accept its fiscal implications?

Germany is serious

Through 2025 and into early 2026, Berlin accelerated approvals and contracting, with defense spending approaching €80-90 billion and a rising share directed toward equipment. Advance payments and multi-year commitments have enabled firms such as Rheinmetall to expand ammunition and air defense capacity. Germany’s new procurement acceleration law - the Bundeswehrbeschaffungsbeschleunigungsgesetz - seeks to compress timelines, even if its name suggests bureaucracy dies hard.

The fiscal architecture has shifted as well. The €100B special fund for the Bundeswehr and greater borrowing flexibility have created near-term space for rearmament without immediate cuts elsewhere. But that window is finite: once the fund is exhausted, elevated spending must be embedded in the core budget and in Germany’s fiscal culture.

The more consequential shift is industrial. When the defense ministry awards €536M in strike drone contracts to Helsing and Stark, with potential follow-on tranches pushing the total toward €4.32B, it is not simply buying hardware. It is conferring market validation. That validation attracts private capital, often in multiples of the original contract. Government becomes buyer of first resort. Investors finance expansion. Supply chains localize. Talent concentrates.

This is how industrial gravity forms. Energetics production, advanced components, robotics integration, and secure software increasingly need to sit domestically for resilience. The dynamic resembles the US AI buildout, where large-scale investment in compute triggered reshoring of semiconductor fabrication and energy infrastructure. Defense, like AI, generates similar downstream pull.

Meanwhile, the rest of Europe risks underestimating how quickly that gravitational effect can consolidate Germany’s advantage.

If you are not tested in Ukraine, you are not serious

This was one of the clearer takeaways from Munich. Operational credibility now determines status. Systems deployed and iterated in Ukraine command attention while those that remain untested struggle for relevance. Survivability under electronic warfare, speed of iteration, and demonstrated impact increasingly define reputation.

Indeed, Ukraine has become Europe’s sorting mechanism. It has also exposed the physics of modern war: ammunition, interceptors, drones, armored vehicles, and replacement systems are recurring expenditures consumed at a tempo measured in weeks and months. And this is where rearmament could slow.

Defense companies will not invest in new production lines unless they believe demand will persist beyond the immediate crisis. Governments, however, remain largely in emergency mode, purchasing finished hardware in large batches for delivery, stockpiling it, or transferring it to Ukraine.

The question is what follows the first wave. If a country acquires 100,000 strike drones but does not deploy them, the timing and scale of the next contract become uncertain. In the interim, production lines slow or require subsidy. If the next conflict demands 500,000 rather than 100,000, Europe must decide whether it prefers warehouses of depreciating inventory or factories capable of sustained surge output.

Rearmament built on episodic hardware purchases will struggle to scale unless procurement evolves.

From buying equipment to buying capacity

The initial procurement surge was necessary. The harder transition is from emergency buying to structural capacity.

A more durable model may resemble cloud infrastructure rather than traditional arms purchasing. Instead of procuring only finished inventory, governments could contract for guaranteed production capacity, paying to maintain throughput and activating full-rate output when required. In cloud computing, customers distinguish between spot usage and reserved capacity. Defense procurement may require a similar distinction between stockpiled hardware and maintained surge capability.

Paying for capacity rather than only inventory aligns incentives with permanence. It enables firms to invest in workforce and supply chains without relying on irregular mega-orders and reduces the risk that expanded lines contract once urgency fades.

If Europe intends rearmament to be structural rather than episodic, procurement models must reflect that intent.

Welfare versus warfare

The fiscal constraint remains central and the United Kingdom offers a cautionary example. Commitments to raise defense spending toward 2.5% of GDP have been prominent, yet debates about deployable mass and readiness persist:

The contrast with the Europeans is becoming embarrassing. The [British] army will have 148 Challenger 3 battle tanks by 2030 but currently has more operational command headquarters than it does artillery pieces, having given 19 howitzers to Ukraine and replaced them with just 14 guns. In contrast, Poland will soon have 980 tanks and 685 self-propelled guns. Finland can mobilise 300,000 troops. Britain’s regular and reserve army totals only 90,000.

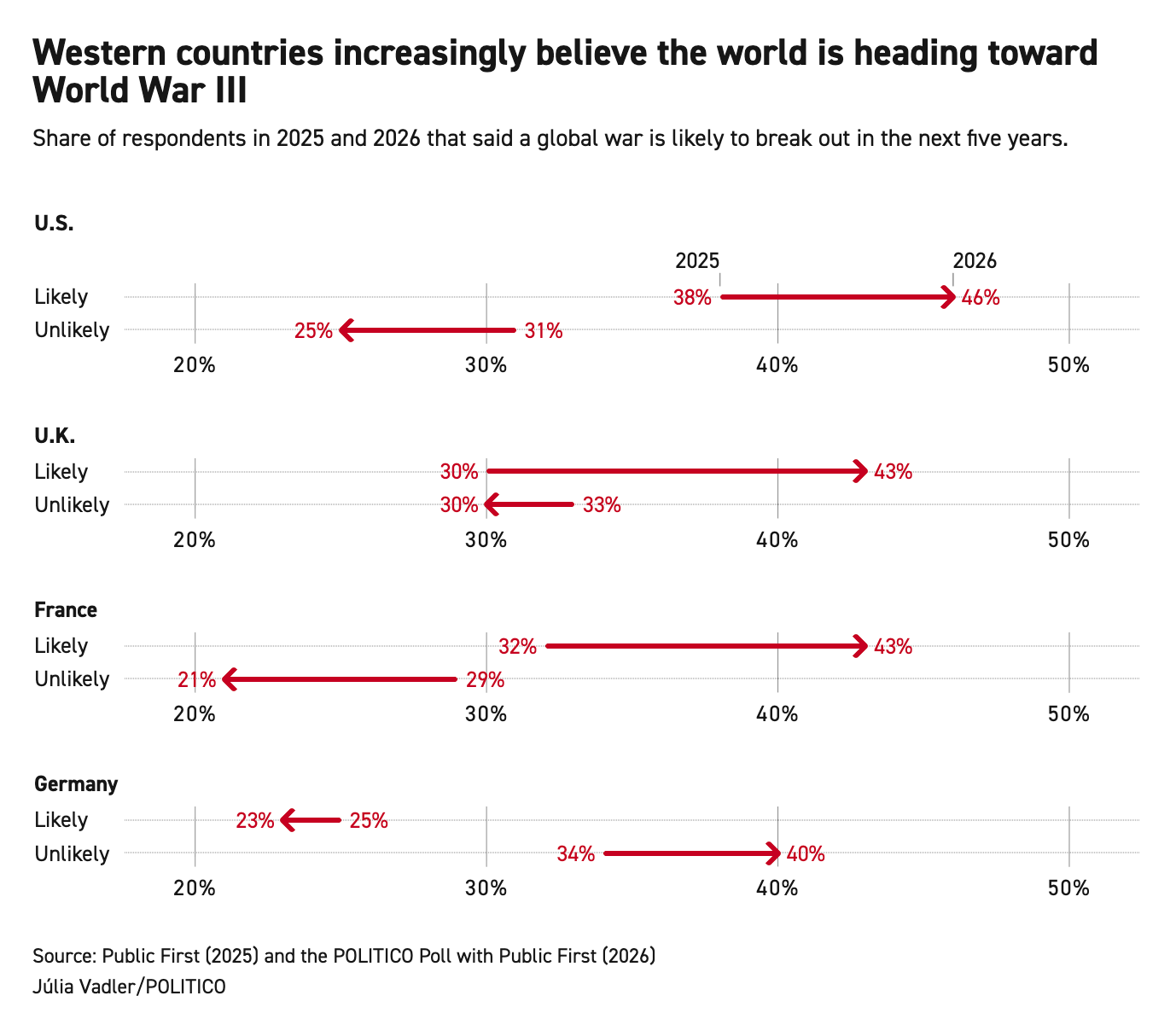

Across Europe, polling suggests that voters increasingly believe the world is becoming more dangerous:

As a result, a large proportion of citizens in Canada, the UK, Germany, France and the US support higher defense spending in principle. But when that support is framed in terms of higher taxes, increased borrowing, or reductions in social spending, voter support falls. For example, in Germany defense spending is one of the least popular uses of government funds, topped only by overseas aid. In the last year, voter approval for defense spending subject to these tradeoffs drop from 40% to 28% in France and 37% to 24% in Germany.

That gap defines the central structural challenge. Rearmament at 3-5% of GDP is not incremental: it represents structural reprioritization within economies built around expansive welfare states. Governments can announce multi-year defense plans and approve emergency packages. Sustaining elevated baselines requires durable consent across electoral cycles and economic downturns.

Without that consent, industrial expansion rests on fragile foundations.

Allies, exports, and domestic priority

Another tension receives less attention: balancing support for allies with domestic resilience. In peacetime, exports reinforce alliances and sustain scale. In wartime, priorities shift. Following the October 7 attacks, Israel redirected production toward domestic requirements, and debates over US munitions supply underscored how quickly allied dependence can become politically sensitive.

When conflict escalates, self-defense takes precedence. If multiple European states were drawn into high-intensity conflict simultaneously, their industrial bases would face similar allocation pressures. Fiscal durability is one constraint. Production allocation under stress is another.

Sharing the upside?

If governments are committing multi-year contracts that de-risk entire sectors, they may also reconsider how value is distributed.

Taking minority equity stakes in companies receiving substantial public contracts would align incentives and allow taxpayers to participate in long-term upside when early demand is state-driven. When the state acts as customer of first resort and absorbs initial risk, it is operating as a strategic investor. Sharing in long-term returns reflects that reality.

Cultural legitimacy

One striking shift in Munich, reinforced in conversations with engineers and AI researchers in Zurich, concerned talent sentiment. A year ago, many technical candidates were hesitant to work on defense. This year, defense work is increasingly viewed as necessary and technically serious, particularly in autonomy, AI, robotics, and advanced manufacturing.

Cultural normalization is a precondition for scale. Europe cannot expand its defense production base without attracting the software and systems talent that previously defaulted to consumer or enterprise sectors.

Europe’s fiscal test

Munich 2025 marked the end of complacency. Munich 2026 clarified the next phase.

Ukraine defines operational credibility. Germany is reshaping Europe’s industrial center of gravity. Procurement models remain misaligned with permanence. Public support weakens once tradeoffs become explicit.

Europe possesses the resources, technology, and industrial base required to rearm. The decisive question is whether it can reconcile warfare with welfare not for a single budget cycle, but for a generation.

Rearmament can survive crisis. Whether it survives normal politics will determine Europe’s strategic trajectory.