Can AI discover new science?

New AI research systems are beginning to contribute verifiable results across mathematics, physics, biology, and materials science. How close are we to AI producing genuinely new scientific knowledge?

The thinking game

A central question has shaped the AI-for-science debate: does AI merely reproduce the knowledge it is trained on, or can it generate new knowledge altogether? Over the past year, this question has shifted from theoretical to empirical. Advances in reasoning models, agentic systems, and autonomous research pipelines mean AI is beginning to function as an accelerator of scientific discovery.

At the national level, the United States has just launched the Genesis Mission, an attempt to build a scientific infrastructure in which AI helps drive simulation, data analysis, and experimental workflows. At the system level, platforms such as FutureHouse Kosmos and AI Scientist-v2 automate increasingly more of the research workflow. And at the level of active scientific projects, frontier models such as GPT-5 are already contributing concrete, verifiable steps across mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology, and materials science, as documented in OpenAI’s Early Science Acceleration Experiments.

In the State of AI Report 2025, we predicted that “open-ended agents will make a meaningful scientific discovery end-to-end.” Whether this happens this year or next matters less than the trajectory now clearly forming. Let’s dive in.

Reasoning models enter the scientific workflow

GPT-5 provides the clearest evidence that frontier models are beginning to contribute genuinely useful scientific support. In mathematics, GPT-5 contributed to four new results on previously unsolved problems, including a novel inequality in high-dimensional geometry, a new approach to a combinatorial question, and two further propositions derived from GPT-5’s candidate lemmas and proof sketches. All were verified by human experts. In one case, the model suggested a structural transformation that unlocked a proof direction that researchers had struggled to identify.

Outside mathematics, GPT-5’s contributions are smaller, but concrete nonetheless. In plasma physics, the model identified a symmetry in a simulation that the researchers had overlooked, leading to a corrected interpretation. In quantum systems, it traced a subtle boundary-condition error through a codebase. In astronomy, it proposed a new re-weighting method for exoplanet transit data that outperformed the team’s heuristic baseline. In computational biology, it redesigned an RNA modelling pipeline by replacing a Monte Carlo routine with an analytic approximation retrieved from literature. And in materials science, its alternative density-functional formulation reduced runtime by more than an order of magnitude.

To be clear, these contributions are not considered independent breakthroughs. But they do demonstrate that GPT-5 can produce intermediate reasoning steps that specialists accept as correct and sometimes useful. In this way, the role of the model is increasingly to explore large hypothesis spaces and propose candidate structures. Humans continue to supply intuition, constraints and verdicts. And that’s genuinely useful.

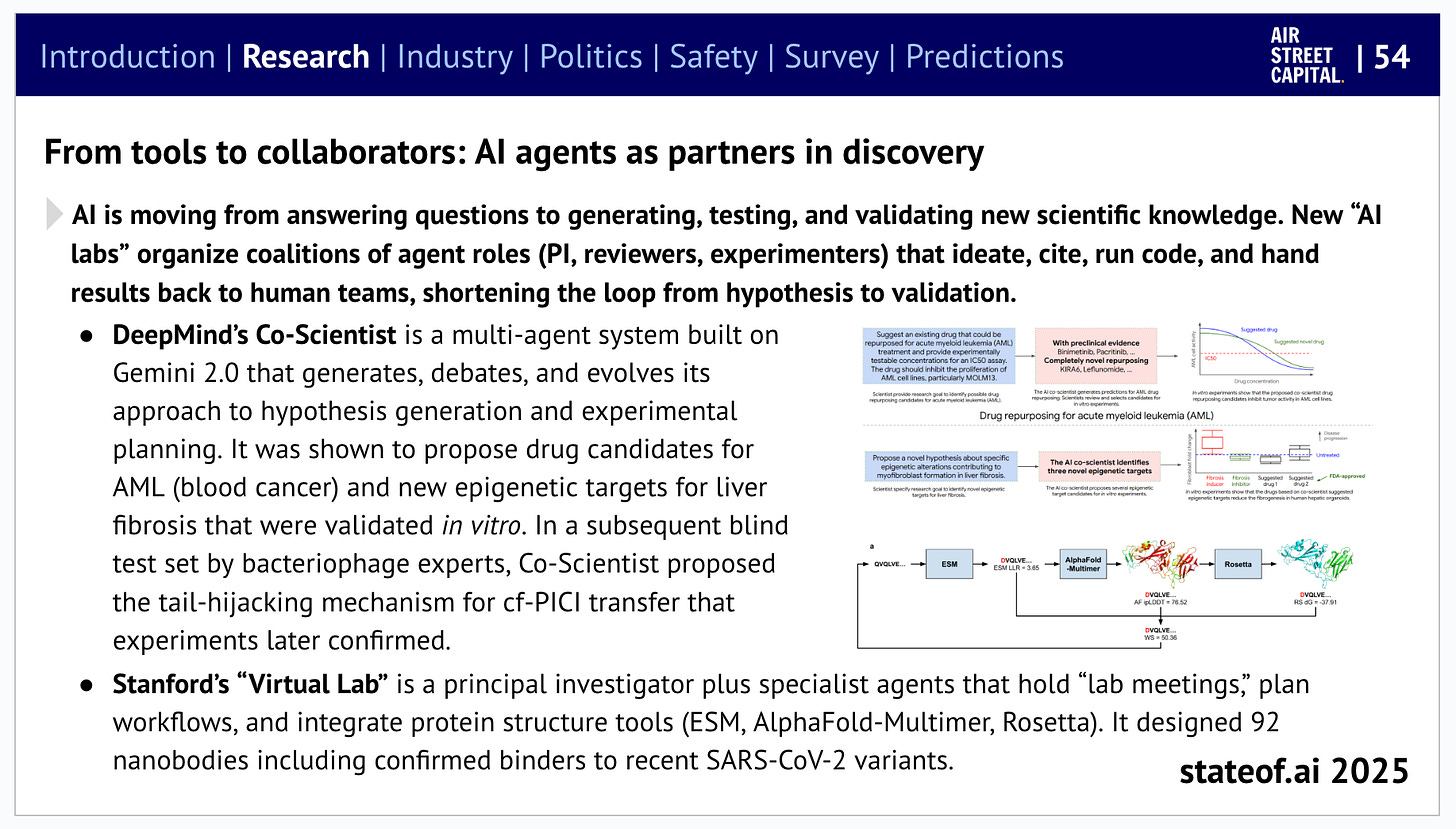

System-level “AI scientists”

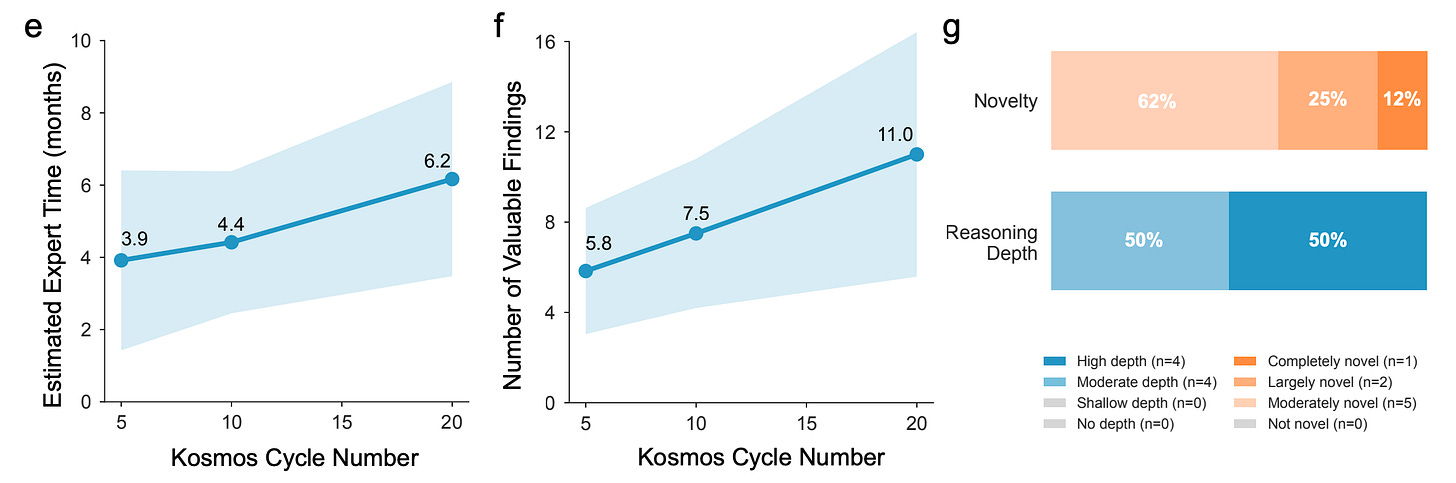

Where GPT-5 demonstrates the power of a single reasoning engine, system-level architectures such as Kosmos show how these models behave inside orchestrated research workflows.

A typical Kosmos run lasts around 12 hours, ingests ~1,500 scientific papers, and generates ~42,000 lines of code across data analysis, simulation, and visualisation modules. The result is a structured scientific artefact linking claims directly to the evidence that supports them.

Crucially, Kosmos has now undergone structured external evaluation. Independent PhD-level reviewers examined 850 claims from Kosmos outputs. They judged 79.4% to be supported by the underlying evidence. Support rates were 85.5% for data-derived claims and 82.1% for literature-derived ones, falling to around 60% for cross-domain hypotheses, the hardest category and the one most associated with novelty.

The case studies reveal both the system’s promise and its current limitations. In one run, Kosmos assembled a multi-step hypothesis connecting SOD2 enzymatic activity to oxidative-stress compensation in tumor microenvironments. Reviewers agreed that many sub-claims were coherent and literature-supported, but disagreed on whether the integrated mechanism was genuinely new. In materials science, Kosmos proposed a plausible relationship among defect energetics in perovskites, again judged likely correct but not obviously novel.

The evidence suggests that Kosmos can generate structured, evidence-linked scientific reasoning at scale, but that its ability to consistently produce new insight remains to be proven.

By contrast, AI Scientist-v2 is entirely in silico. It conducts machine-learning research end-to-end on standard benchmarks, designing experiments, running code, analysing output, and drafting manuscripts. In Sakana’s evaluation, one of three fully AI-generated papers passed the reviewer acceptance threshold at an ICLR workshop. This demonstrates autonomous research capability in computational domains, not physical scientific discovery.

A national AI stack for scientific discovery

The US Government’s recently announced Genesis Mission represents the most ambitious federal effort to date to build a national AI-enabled scientific capability. As laid out in the Presidential Action, Genesis aims to create a unified platform that integrates the Department of Energy’s scientific user facilities, national laboratories, high‑performance computing centers, and decades of federally funded datasets into a single AI‑accelerated research ecosystem.

The mission directs federal agencies to develop scientific foundation models, deploy AI agents capable of generating and testing hypotheses, and expand autonomous laboratory systems across priority domains including fusion energy, advanced nuclear technologies, climate and Earth system modelling, biomedicine, drug discovery, materials science, and grid resilience. It also establishes a new governance framework to manage safety, provenance, and access to these AI systems. Lastly, the project reflects a geopolitical shift in which scientific competitiveness - and national resilience - are tied to the strategic integration of AI across the full stack of discovery.

How scientific practice is beginning to change

These developments are already reshaping aspects of the scientific method.

One shift is toward executable research. Kosmos and AI Scientist-v2 generate artifacts where claims are linked to code and data, creating a computational form of reproducibility. Another shift is the emergence of abundant machine attention. Systems like GPT-5 and Kosmos can sweep literature and simulation spaces at scales impossible for humans, shifting the bottleneck from idea generation to physical validation.

Research groups may also evolve into hybrids of human and digital labor. Instead of relying solely on students and postdocs, labs may soon supervise persistent fleets of agentic researchers. Finally, verification becomes the central constraint. While some fields provide clean verifiers, biology and medicine do not, yet these remain the domains with the greatest pressure to adopt AI.

So, how close are we to AI creating new knowledge?

Taken together, GPT-5, Kosmos, and AI Scientist-v2 provide a picture of meaningful but incomplete progress. GPT-5 has already contributed new results in mathematics and useful reasoning steps in multiple sciences. Kosmos produces large volumes of mostly correct scientific reasoning, with occasional glimmers of novelty. And AI Scientist-v2 shows that autonomous research is possible in constrained computational domains.

But none of these systems constitute a general-purpose scientific discoverer just yet. The frontier remains uneven across domains, and the line between new insight and recombination remains difficult to draw. The most defensible position today is that AI is beginning to accelerate scientific discovery and, in some aspects, originating it. And that is meaningful.

The path ahead

Whether open-ended agents achieve the State of AI Report 2025 prediction this year is almost beside the point. It is a matter of time. As Demis Hassabis has argued, the point of building increasingly general AI systems is not to automate what scientists already do, but to expand the scientific frontier itself. AlphaFold was the first demonstration that AI can deliver solutions to problems that resisted decades of human effort. The systems emerging today extend that logic: they explore hypothesis spaces humans cannot hold in mind, recognise structures we overlook, and recombine knowledge at scales that make new questions thinkable.

The trajectory is clear. For the first time, we are witnessing the early phases of a scientific ecosystem in which ideas, experiments, and interpretations emerge from a hybrid of human and machine intelligence. The systems deployed today are imperfect, uneven across domains, and still fundamentally dependent on expert oversight. Yet they mark the beginning of a shift in the practice of science that is unlikely to reverse.

I believe it will work in 1-2 years

Thanks for this thoughtful exploration of the potential applications of AI to scientific discovery. This topic is having a moment. Consider the $300 million seed round raised by Periodic Labs, which is aiming to build AI-driven automated laboratories to make discoveries in the physical sciences. And the bill introduced in the U.S. Senate yesterday to create a "National Network of AI-Enabled, Automated Labs." (See https://www.fetterman.senate.gov/fetterman-budd-introduce-legislation-to-create-first-national-network-of-ai-enabled-automated-labs/.) This is a super exciting topic.