Real talk on funding gaps

An industry sitting on $20 billion of dry powder doesn't require government subsidy

In the course of our work advocating for pro-innovation policies, we regularly interact with UK government stakeholders. One of our long-standing arguments is that the government should focus less on subsidizing the technology sector and more on other interventions.

These include:

Resolving structural barriers (e.g. visa rules for talent);

Building the right infrastructure (e.g. building out a proper national compute cluster);

Acting as a customer (e.g. fixing procurement).

Anyone who’s spent time on the UK technology, life science, or venture scenes will be aware of the ‘funding gap’ discourse. The argument essentially runs as follows: the UK is a great place to attract early-stage investment, but when you reach Series B, you will hit up against a lack of domestic capital.

As a result, promising companies either fail to get through their growth stage or have to turn to deep-pocketed US investors. Sam Gyimah, UK science minister turned venture partner at Lakestar, went as far as saying that the UK faced a $1.8 trillion funding gap. As a result, the government needs to step in and ‘catalyze investment’ (read: ‘prop businesses up with taxpayers’ money’).

We frequently heard this argument when we were campaigning for spinout reform. The failure of more than 95% of university spinouts to raise more than £25 million was not because universities had sabotaged them through a flawed process. Instead, it was because of a funding gap in [insert incredibly well-capitalized sector of your choice].

This always confused us, because we’d read about these funding gaps in the same newspapers that would run stories about record volumes of VC ‘dry powder’.

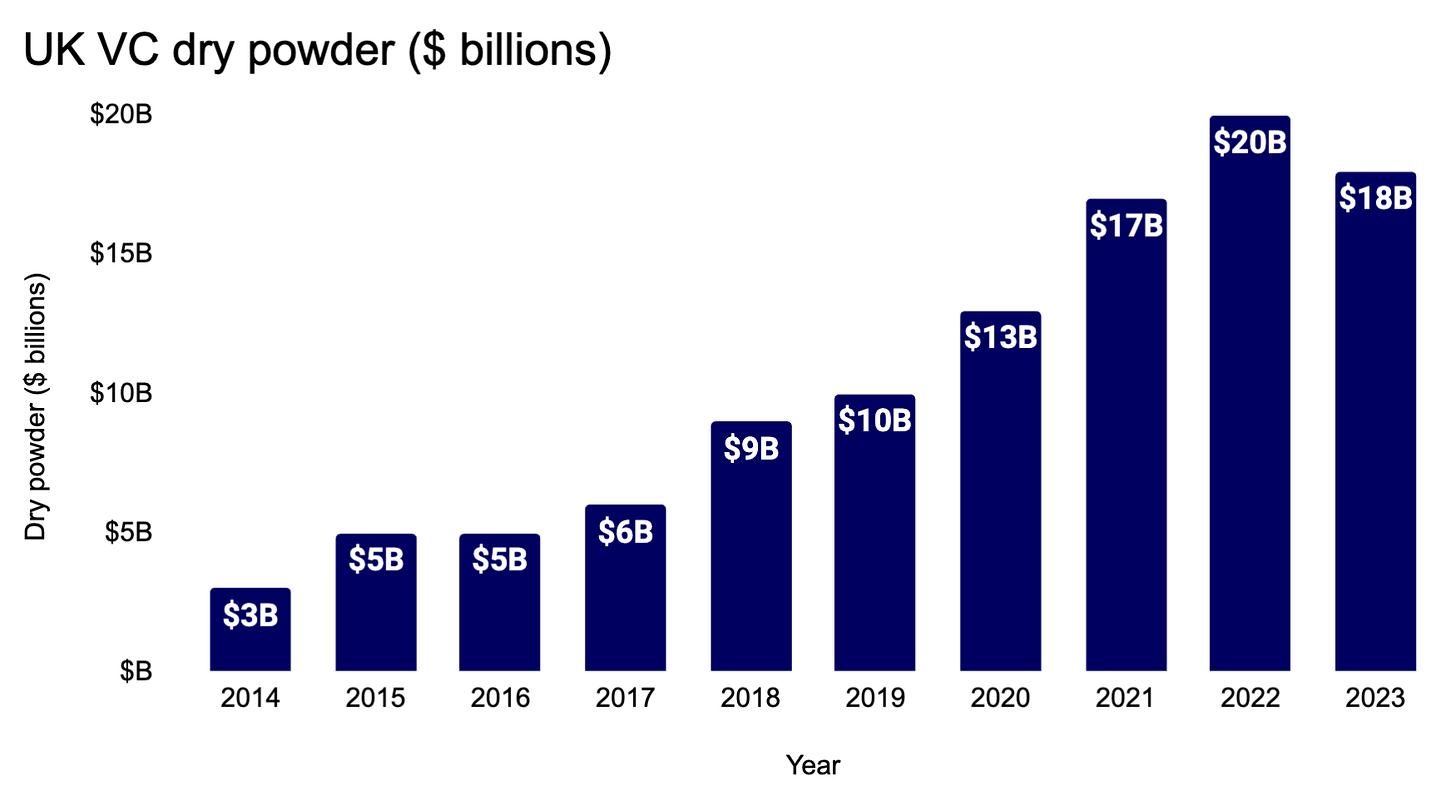

Our friends at Dealroom have helpfully compiled data showing that UK VCs are currently sitting on $18 billion of unspent money - twice as much as five years ago.

Source: Dealroom and Air Street Capital analysis

The notion that an industry with this much capital at its disposal is unable to lead B or C rounds without the government stepping in isn’t credible. So what’s going on?

A stop gap excuse

Firstly, we think ‘funding gaps’ offer a comforting defeatism. By underpricing the potential impact of difficult institutional change, whether it’s capital markets reform or improvements to procurement, we can convince ourselves that the problem is out of our hands. It’s easy to lament that we can’t all be as rich as the US. Getting out the cheque book is easier than rewiring the operating system, no matter how ineffective it usually is.

Secondly, it’s straightforward lobbying for grant money. While the UK government rightly valorizes its science and technology sector for the quality of its output, the companies are motivated by the same incentives as other parts of the economy. We saw first-hand just how aggressively universities fight for their short-term commercial interests. If lobbying the government gets you free money, you’ll do it.

Finally, a refusal to accept the basic reality of free markets. The majority of venture-backed companies will not succeed and we would expect many of them to fail at the ‘funding gap’ stage. Good technology can fail to achieve product-market fit. A company’s storytelling may fail to persuade customers or investors.

Someone else can come along and build something better or more quickly or get to customers faster…or all three!

While regrettable for everyone involved, it’s not a market failure the government needs to correct. In fact, it’s a sign that the market is functioning properly.

Throwing good taxpayer money after bad VC money is not only wasteful, it’s actively harmful to the ecosystem. It distorts investment by creating a false demand signal and locks talent into businesses with weak long-term prospects.

By contrast, Silicon Valley accepts entrepreneurship as a high-risk path. There are many successful founders who initially experienced failure, before going on to build something better. If the government had stepped in to catalyze investment and keep their first business afloat, even after it had failed commercially, the later success would never have been born. This comes with a staggering opportunity cost in human potential.

It often feels like governments are acting on an outdated model of the VC ecosystem. 10-15 years ago, the venture industry in the UK was genuinely very small and the government played an important role in bringing it to life.

However, times have changed. Instead of backstopping investors that can afford to stand on their own two feet, governments should focus their attention on the policy barriers they are uniquely placed to address.