Learning from execution: Sereact's Cortex 1.6 and real-world robotics

Why execution-level learning changes how robots improve in production.

AI has progressed fastest where the world can be cleanly digitized. Language, images, and code have all benefited from large models trained on vast, diverse datasets. The physical world, with its unstructured dynamics and long-tail edge cases, has proven far more challenging. Social media is filled with impressive robotics demos, yet many of these systems struggle outside tightly controlled environments, or rely on hidden teleoperation and task-specific tuning.

The bottleneck today is less about perception, planning, or control in isolation. Those capabilities largely exist. The challenge lies in the brittle interfaces that bind them together. Traditional robotics stacks rely on hand-engineered pipelines where perception feeds symbolic state into planners, which then dispatch actions to controllers. Each stage encodes assumptions that break under real-world variation. When they do, failures are physical, costly, and difficult to recover from.

A growing class of robotics efforts aims to replace these brittle interfaces with learned systems trained directly on real interaction data. One of the more compelling examples is Sereact, a Stuttgart-based robotics company deploying learning-based manipulation systems in live production environments. This essay examines Sereact’s Cortex, and in particular Cortex 1.6, as evidence that robotics may be entering a new phase of learning-driven progress.

Cortex treats manipulation as a learning problem end to end because learning should determine how sensory inputs are translated into actions, especially under real-world variation. Cortex 1.6 strengthens this claim by changing how learning signal itself is extracted.

Why robotics has resisted scaling

Robotics is uniquely unforgiving. Language models can hallucinate. Coding agents can stumble and try again inside a virtual machine. Robots drop objects, collide with equipment, or endanger nearby people. Small errors often cascade into failure.

Historically, the field narrowed the problem to achieve robustness. Robots were deployed in highly structured environments and tuned for fixed tasks. When variation crept in, engineers patched systems with heuristics, additional sensors, or narrowly targeted data collection. Over time, these stacks grew complex, fragile, and expensive to maintain.

By contrast, frontier models in other domains improved by absorbing variation through scale. Instead of encoding rules for every edge case, they learned directly from large and diverse data distributions. Robotics largely missed this shift because large-scale interaction data was difficult to collect, expensive to label, and hard to reuse across deployments.

Sereact Cortex: a vision-language-action (VLA) model

Cortex is a vision-language-action model trained to map sensory inputs directly to robot actions, bypassing brittle intermediate abstractions. Instead of separating perception, planning, and control into independently engineered modules, Cortex learns the full loop as a single system.

Crucially, this learning takes place on real robot interaction data collected across tasks, objects, and environments within customer facilities. The underlying hypothesis is that generalization emerges from exposure to sufficient diversity, and that failures should be incorporated into learning rather than handled as special cases downstream.

This stands in contrast to how most robotic systems learn today. In many production systems, learning is driven by sparse terminal outcomes. A task either completes or it does not, and learning happens after the fact. In physical systems, this abstraction is limiting.

Learning from execution, not just outcomes

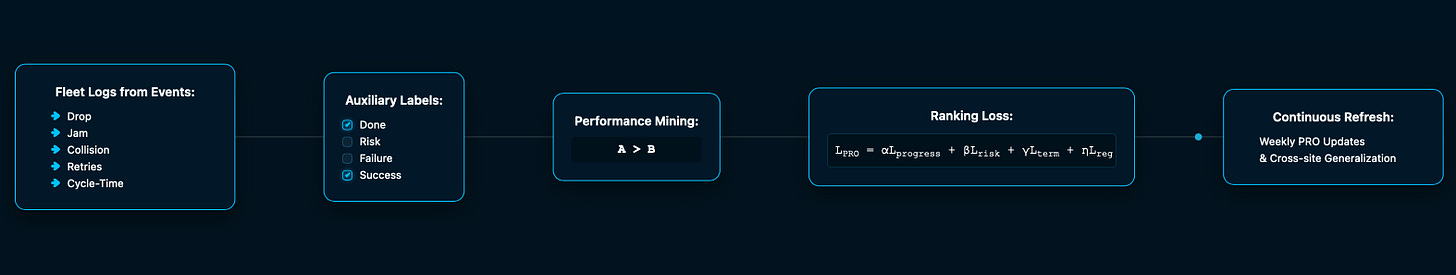

Cortex 1.6 changes how learning signal is obtained. Instead of relying solely on hand-engineered rewards or terminal success labels, it introduces a learned Process-Reward Operator that evaluates execution as it unfolds.

Rather than asking only how a task ends, the system continuously assesses how it is progressing. Signals related to stability, completion likelihood, and risk are inferred from raw operational telemetry such as motion dynamics, force profiles, retries, and recovery behavior. This allows reinforcement learning to operate on dense, process-level feedback grounded in real execution rather than sparse post hoc outcomes.

Importantly, this reward model is trained entirely from real deployment data. That reflects a core advantage of Sereact’s approach: a fleet of robots operating continuously across third-party logistics, warehousing, e-commerce, and manufacturing environments provides a steady stream of high-fidelity interaction data.

Outcome-based learning collapses rich execution dynamics into a single label. Smooth executions and fragile recoveries are treated as equivalent if both succeed. By contrast, execution-aware learning can reinforce behavior that completes tasks with margin and suppress behavior that relies on late or unstable corrections, even when both technically succeed.

Because execution itself provides learning signal, improvement can continue during deployment. Optimization shifts away from raw completion rates toward reliability.

Empirical evaluation in production workflows

To evaluate this learning regime, Cortex 1.6 was tested on three live production workflows: pick-and-place, shoebox opening, and returns handling. All data was collected from real deployments. Performance was compared across three systems: a baseline vision-language-action policy trained via imitation learning, Cortex 1.5, which relies on binary success signals and human-triggered policy patching, and Cortex 1.6, which incorporates dense execution-level rewards via the Process-Reward Operator.

Across all tasks, Cortex 1.6 achieves the highest overall success rates, outperforming both the imitation baseline and Cortex 1.5.

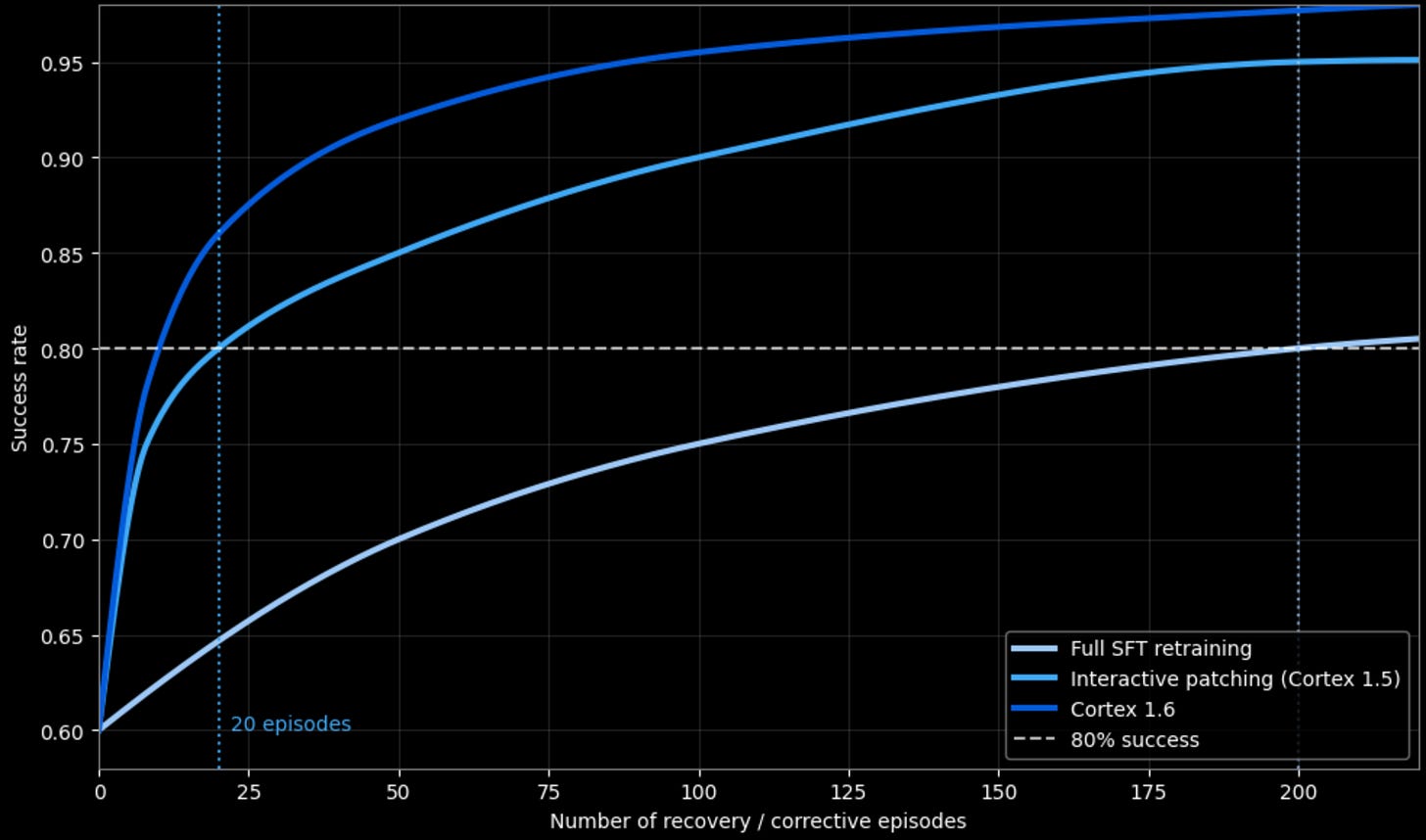

More notably, the introduction of execution-level rewards substantially accelerates learning. Time to convergence is reduced by roughly a factor of two relative to Cortex 1.5, and by more than a factor of three relative to the baseline system.

Improvements are not limited to success rates or learning speed. Recovery behavior improves materially. After an initial failure, recovery success increases from approximately 45% in the baseline system, to around 65% with Cortex 1.5, and to roughly 80% with Cortex 1.6. Average task retries per episode fall by 30-50% after training with execution-aware rewards.

What the numbers mean

Taken together, the results support three empirical conclusions.

First, Cortex 1.6 demonstrates robust generalization under real operational conditions. Performance gains persist across different workflows and under distribution shifts that commonly break deployed systems, including novel objects, clutter, and execution noise.

Second, learning becomes markedly more efficient when reward is derived from execution itself. Replacing sparse terminal feedback with dense, process-level signal reduces the amount of interaction time required to reach high performance. Learning progresses through incremental improvements rather than episodic jumps, even while robots are already deployed.

Third, the gains extend beyond headline success rates. Recovery behavior improves and retries decrease, indicating that the system is learning how to act well throughout a task, not merely how to reach a successful endpoint.

These findings highlight a broader lesson. In traditional robotics learning, sparse or delayed feedback obscures where instability begins and where robustness is earned. By exposing learning algorithms to execution-level signal, Cortex 1.6 changes both what is learned and how quickly it is learned. Reinforcement learning becomes grounded in real operational behavior rather than post hoc outcomes.

If frontier models are to work reliably in the physical world, they must be trained on more than success and failure. Cortex 1.6 offers early evidence that learning directly from execution is a viable path toward robots that are not only capable, but consistently reliable.