PARIMA Achieves a World First for Europe’s Cultivated Food Industry

PARIMA’s achievement should be celebrated in Europe, but also studied as a warning.

PARIMA, a global leader in cultivated proteins, has become the first European company to secure regulatory approval for cultivated meat, with the Singapore Food Agency granting clearance for its cultivated chicken. It’s a historic moment for Europe’s food-tech sector, but one that’s unfolding thousands of miles away from home.

For PARIMA, the approval validates years of research and development, as well as industrial scaling work. The company has built one of the largest cultivated food facilities in the world, developed novel cell lines, as well as bioprocess engineering techniques and infrastructure for scalable production. Its category-leading regulatory portfolio now spans nine active filings across major jurisdictions. Moreover, PARIMA strengthened its supply chain by acquiring a key cell line supplier in the cultivated food ecosystem, Vital Meat, to further consolidate its position as a global leader in next-generation proteins.

But make no mistake: Singapore’s approval is no accident. Since 2019, the city-state has pursued a coherent national strategy for alternative proteins within its broader “30 by 30” food security plan aimed at producing 30% of the nation’s nutritional needs locally by 2030. This includes a predictable, science-led regulatory process and targeted incentives for industrial deployment. The result is a functioning market where new food technologies don’t just pilot. They sell.

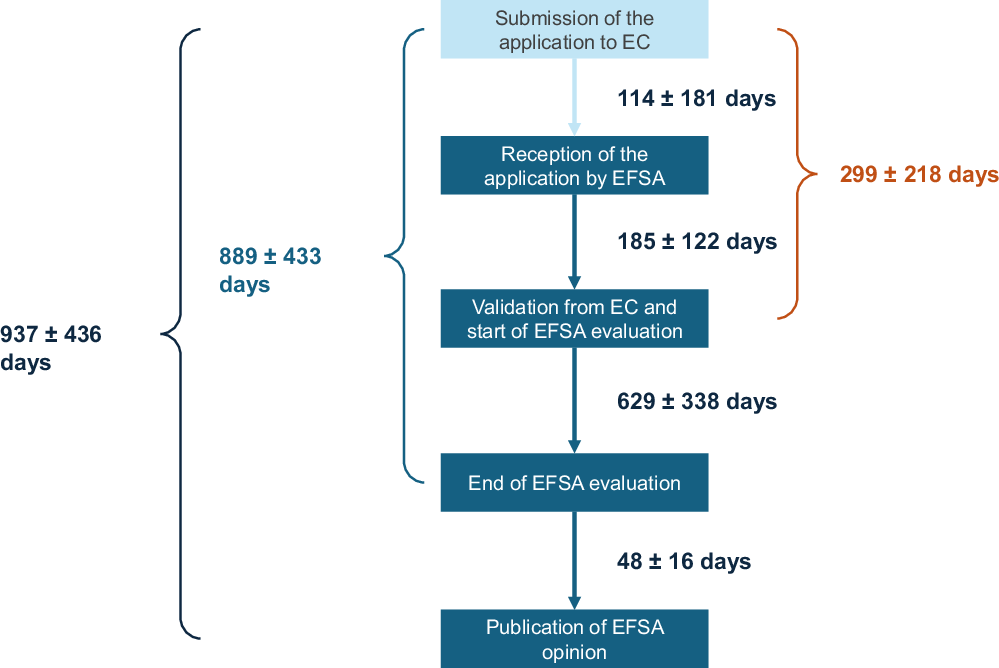

Europe, meanwhile, continues to incubate world-class science without the political will to deploy, buy or scale it. The EU’s novel foods pathway has become a regulatory maze that would challenge the labyrinths of Greek and Minoan civilization in its complexity. According to Nature Food, the average time for approval of a novel food application in the EU now exceeds 35 months - a delay that effectively sidelines startups and deters investment. Worse yet, it rewards incumbents and retards innovation. PARIMA’s approval in Singapore is not a failure of European science. It is a failure of European policy.

Cultivated food is now entering its industrial era. The question is not whether the technology works - it does - but where it will scale. If Europe wants to lead in sustainable food production, it must match scientific excellence with regulatory competence. Otherwise, the continent will remain a laboratory for breakthroughs that commercialize elsewhere. And if Europe is content to let others commercialize its discoveries, it should be honest about that reality.