The defense ‘exit problem’, big pharma, and perverse incentives

We explore the challenge of defense exits in Europe, looking at the lessons the defense primes could take from another oligopoly, before returning to our favorite set of broken incentives.

Introduction

The first phase of our work on European Dynamism and defense examined how the sector was stuck in a doom loop. Thanks to a broken procurement system, new entrants rarely scale, investors see next to no chance of any attractive return on the capital they risk, and founders opt for a surer playbook in the safer lands of SaaS.

We’ll have more to say on procurement reform in the coming weeks, but today, we’re looking at the other side of the market: exits.

There’s been a lively discussion in recent weeks among investors about the ‘exit problem’ in European defense. With lower margins than sectors like enterprise software, potential returns are already structurally more constrained. Add to that the low likelihood of many challengers making it to IPO. The defense primes often don’t pursue tech acquisitions aggressively, while historic consolidation of the buyer universe has narrowed the pool of potential acquirers.

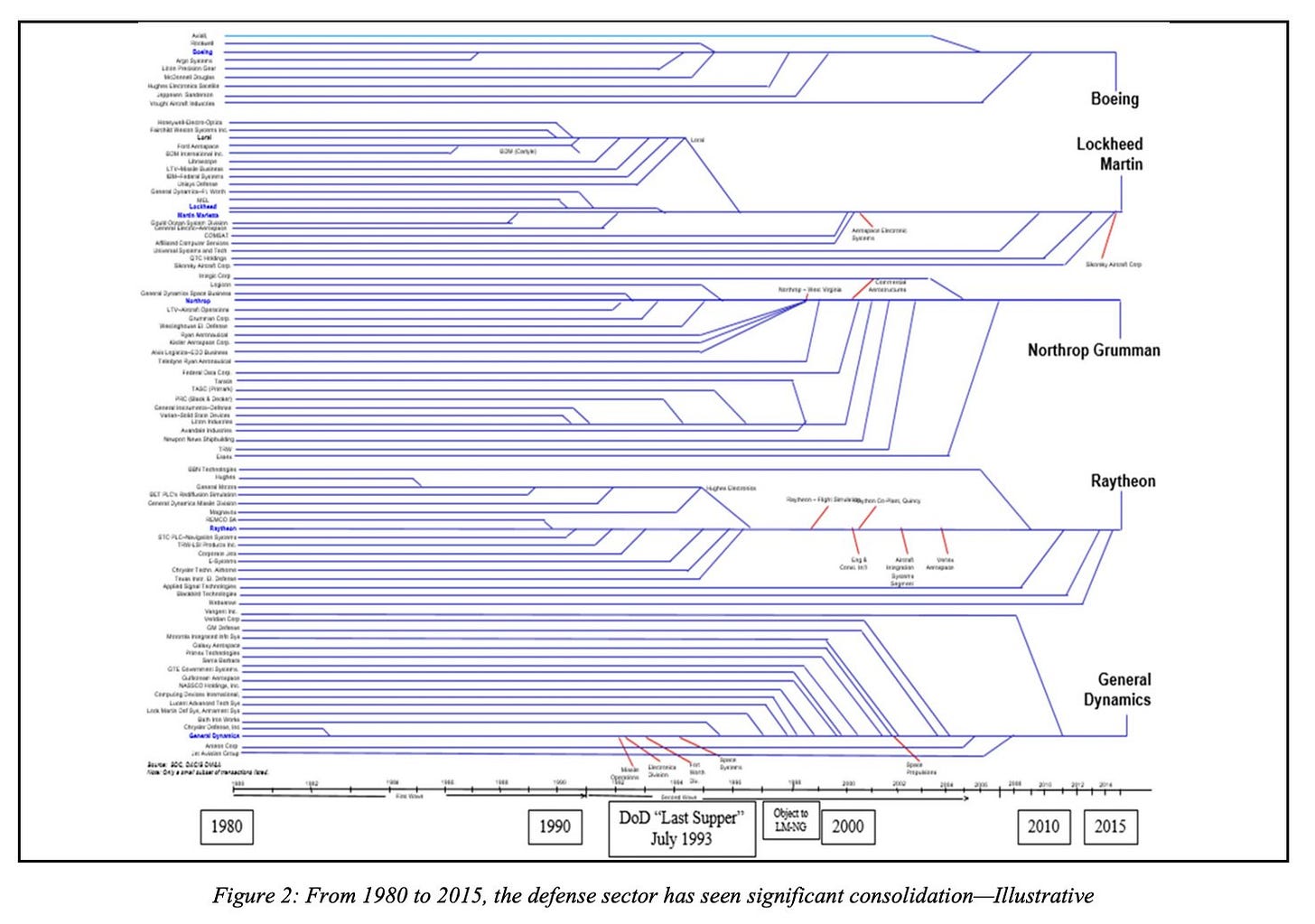

Following World War II and then the Cold War, western governments actively encouraged this consolidation to counter falling demand. This was most famous in the US with the so-called ‘last supper’:

However, the same trend is visible in Europe. For example, BAE Systems is a product of decades of mergers and acquisitions, fusing together at least 12 different companies.

In this piece, we’ll offer a perspective on the barriers to exit, including how the defense primes could move from being the part of the problem to part of the solution.

We aren’t going to spill much ink here on the well-trodden subject of public markets reform, as many others have done this already. Instead, we feel there’s a valuable case study in an apparently different industry, which has some surprising areas of overlap. One where the industry is dominated by a small number of old-school, publicly traded companies with large amounts of cash on their balance sheets that are also subject to strict government regulations when creating and selling new products. We are, of course, talking about big pharma.

Strategic partnerships and an M&A boom

To be clear, we don’t believe big pharma companies are the star pupils of the public company world. They have faced many of the same criticisms as the defense primes, whether it’s anti-competitive commercial practices or focusing too much on dividends and buybacks. When compared to the defense primes, however, they are model corporate citizens.

When big pharma spotted an emerging wave of new start-ups that significantly outclassed its own R&D, it saw an opportunity. The precedent was set in the 1980s by Genentech and Roche. Genentech pioneered and commercialized the field of recombinant DNA technology and is widely seen as the first ever biotechnology company. Back then, while biotechnology was confined to academic research labs, Genentech was out successfully raising venture funding and bringing products to market.

Roche leaned into the opportunity to partner with a business that was beating the rest of the field on R&D. First, it bought the rights to Interferon, a drug for the treatment of hepatitis C and hairy cell leukemia. It similarly bought the marketing rights to Activase, a drug used for treating heart attacks and strokes. As Genentech ran into financial difficulties, Roche purchased a 60% stake in 1990 for $2.1 billion.

While this purchase, and a later complete acquisition, forged closer research ties, Roche was content to allow Genentech to operate as an independent unit with far-reaching autonomy. This allowed it to preserve its culture, ability to attract talent, and flexibility, while benefiting from Roche’s commercial reach and firepower. Genentech is all the stronger for it, poaching academic luminaries to build out a 400-person computational sciences team, while striking a strategic partnership with NVIDIA.

This set a precedent in the industry that other firms soon began to replicate. The entire biopharma industry is predicated on big pharma outsourcing early and very risky R&D to a lively ecosystem of biotech startups that are funded with venture dollars.

Once biotechs demonstrate their ability to discover, design and successfully advance promising medicines to a certain stage of maturity, pharma is more than happy to step in with large acquisitions in the billions - either of companies or individual product lines. This passing of the baton enables promising medicines to be adequately capitalized for large clinical trials and regulatory compliance procedures until they obtain clearance from the FDA such that they can be administered to patients.

In 1993, we saw the number of strategic partnerships between biotech companies and big pharma hit 69, before soaring to 502 by 2004 and continuing to climb. Strategic partnerships then tipped into an M&A boom in the sector. This was combined with healthy R&D investment, averaging out at 20% of annual revenues.

Defense primes underinvest and taxpayers pick up the bill

By contrast, while acquisitions happen in defense, volumes are smaller. Life sciences M&A in 2023 alone hit $191 billion, while the $38 billion for defense was regarded as a good year. Meanwhile, the largest defense firms spend precious little on R&D, especially compared to pharma. We struggled to find a defense contractor that spent over 5% of net revenues, with most sitting at around 2-3%. For example, AbbVie, which is in the middle of the pharma R&D league table, spends more than the three largest defense contractors combined.

Source: Company Form 10-Ks (2022)

While it’s true that pharma companies operate on significantly larger margins, we analyzed the balance sheets of a number of defense primes, and found no shortage of spare cash. Instead, we found those companies were simply more interested in paying out dividends and buying back shares than they were in investing in R&D.

It’s also important not to be taken in by headline R&D investment figures, as defense primes usually pass the cost of R&D back onto the customer. In essence, the taxpayer provides subsidized R&D for multinationals, the product of which is then sold on to foreign customers.

For example, QinetiQ, who we charted as the biggest winner of DASA grants, recorded £328 million of R&D expenditure in 2023, but £313.8 million of this was funded by the customer. QinetiQ naturally paid its shareholders a 2% dividend. Last year, Lockheed Martin returned £9.1 billion to shareholders through dividends and buybacks. Company-funded R&D totalled £1.7 billion in 2022. Similarly, BAE Systems unveiled a £1.5 billion share buyback programme in 2022, while spending £287 million of its own money on R&D.

In 2023, the US Department of Defense conducted a study of defense financing arrangements. Industry representatives claimed that the profitability from government contracts simply wasn’t enough to finance further investment.

The study flatly disagreed finding that: “Despite increased profit and cash flow, defense contractors chose to reduce the overall share of revenue spent on IR&RD and Capital Expenditures (CapEx), while significantly increasing the overall share of revenue paid to shareholders in cash dividends and share by buybacks by 73%”.

Source: Department of Defense: Contract Finance Study Report 2023

A question of incentives

So why has pharma upped its game, while defense hasn’t? There is likely a lack of imagination on the part of the primes, but it’s not the main factor.

In short, there’s been no commercial reason for them to do so. If a pharma business manages to secure a patent on a crucial new drug, this can lock in billions of dollars of revenue for decades, which it would otherwise not receive. Its merits are a discussion for another time, but pharma patents create a winner-takes-all dynamic. This just does not exist in defense contracting.

Due to a desire to preserve jobs and maintain capacity in the industrial base, programmes of record are often divided up among the primes. This makes the competition among the primes a distinctly lower stakes endeavor, while shutting out challengers. There are almost no circumstances in which governments would allow these businesses to fail - no matter how often they fail to deliver.

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, the incentive to engage with start-ups at scale - whether that’s through investment, licensing, or acquisition, will only come when the customer rewards innovation.

As we established in our previous report, efforts to increase the proportion of defense spending directed to smaller businesses benefits plumbers and electricians who happen to operate near military installations, but it does little to modernize capabilities. However we cut the problem, whether it’s entry or exit, we end up back in the same place. Fundamental reform is unavoidable and anything short of this is wishful thinking.

Multi-billion dollar companies aren’t going to spontaneously cut their buyback programs to focus on R&D out of patriotism. Start-ups are going to struggle to disrupt them when the front door remains sealed shut.

We will continue to speak out on this issue and invite anyone who agrees with our mission or is working on an idea in this space to get in touch.