Europe woke up from its security slumber at Munich in 2025. Now it has to deliver in 2026.

Europe has money, talent, technology, and a new sense of urgency. It needs to re-learn scaled production and how to fight at speed.

The vibe shift

Europe’s security assumptions changed decisively in 2025. The Munich Security Conference marked the moment when American security guarantees were no longer treated as automatic, and Ukraine ceased to be an exception to Europe’s defense model, which had by this time expired.

Since then, defense spending across European NATO members rose sharply, with total outlays moving toward €380-400B and procurement spending rising far faster than budgets overall. More than twenty countries increased defense spending, many by double digits. What had once been treated as a ceiling became a floor.

What has not yet sufficiently changed, however, is how Europe actually builds and buys weapons, and the distance between announced intent and delivered capability remains wide.

The political constraint has lifted

In spending terms, 2025 marked a break with the past. A growing bloc of European states - led by Poland and several Baltic and Nordic countries - began openly backing defense spending levels closer to 5% of GDP over the medium term, pushing the long-standing 2% benchmark from target to baseline. At the EU level, new procurement instruments such as the €150B Security Action for Europe (SAFE) facility saw Brussels motivate direct industrial enablement.

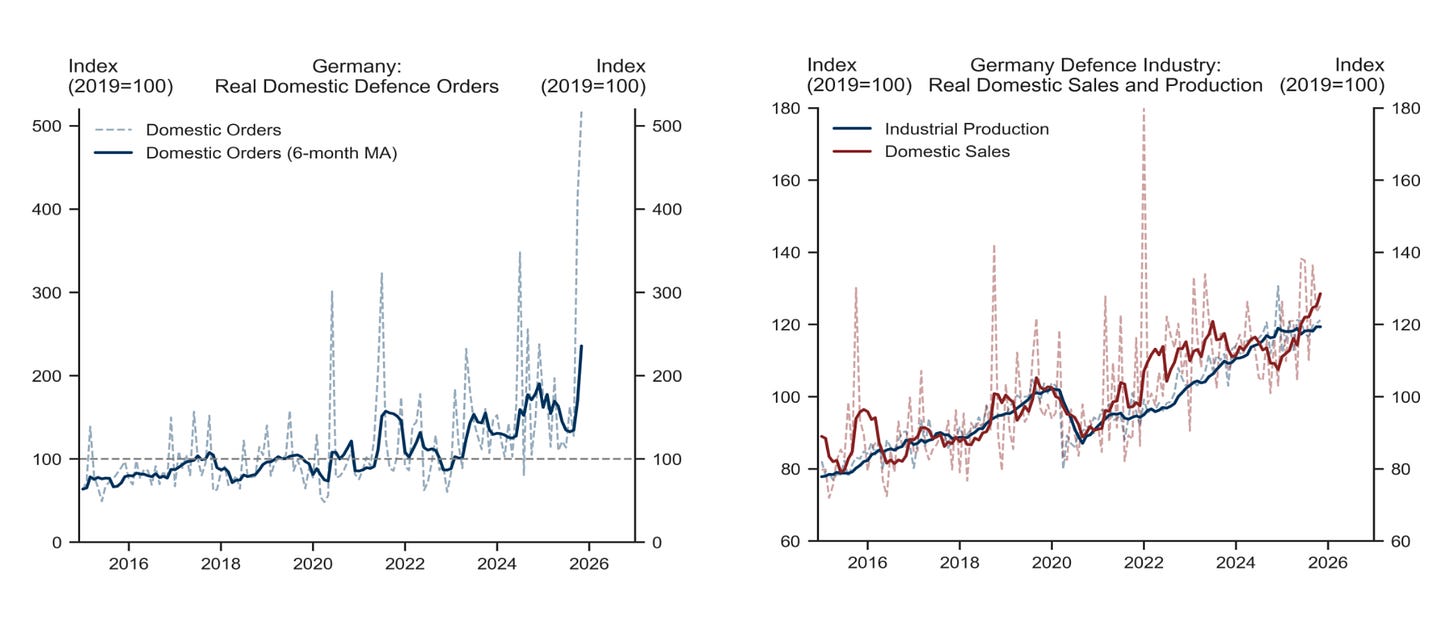

The political argument over whether Europe should spend largely collapsed, even if delivery remained uneven across countries. The harder question became what that spending could actually buy, and how quickly it could be turned into usable military capability. Germany illustrates the constraint. Between 2025 and early 2026, the six-month moving average of domestic defense orders rose by roughly 2x, while domestic sales increased by about 25%. Industrial production, by contrast, edged up only marginally over the same period, highlighting how quickly demand is now outpacing output.

A defense base built to manage decline

But, Europe ran into the production gap almost immediately. The war in Ukraine’s high-intensity fighting consumes immense amounts of artillery shells per day, along with drones, interceptors, and spare parts, at rates that invalidate peacetime assumptions. By late 2025, the EU and its member states had together provided more than €60B in cumulative military assistance to Ukraine since 2022, much of it drawn directly from European stockpiles. But fresh military allocations in 2025 were far smaller - on the order of only a few billion euros - underscoring the gap between cumulative support and the pace of new production. Europe’s defense industry was not built for this environment: it was built to manage decline post-World War 2 and the Cold War. That legacy reflects decades of unpredictable demand, stop-start procurement, and capital discipline that rewarded efficiency and predictability over stockpile and surge capacity.

The UK offers a clear case study. Detailed analysis of British defense procurement shows a system optimised for procedural compliance rather than delivery, with shifting requirements, program churn and weak accountability for delay. Large programs arrive late and compromised, while smaller suppliers struggle to navigate acquisition pathways designed around legacy primes.

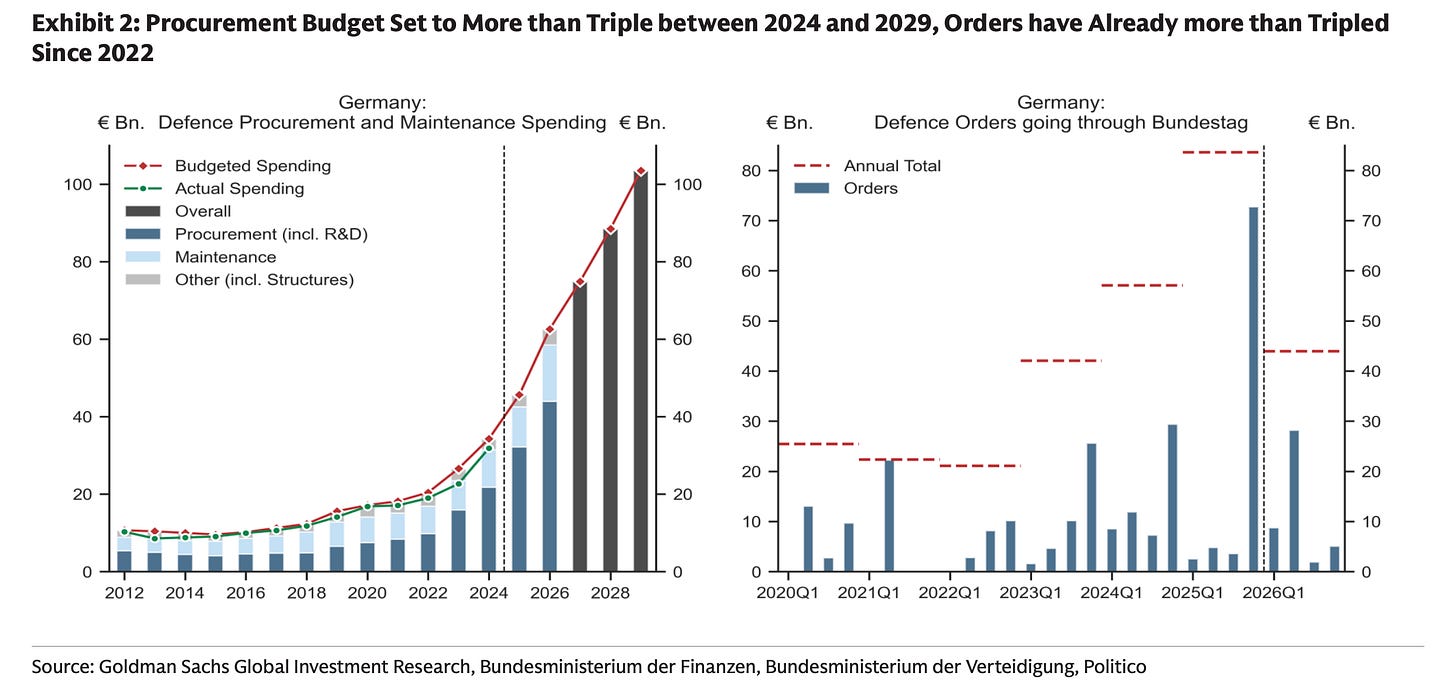

Germany, again, exhibits a different dynamic. In 2025 it accelerated approvals and contracting by passing the Bundeswehrbeschaffungsbeschleunigungsgesetz (literal translation Federal Armed Forces Procurement Acceleration Act) - a procurement‑acceleration law whose ambition to simplify process was clearer in intent than in nomenclature. Defense spending rose to nearly €80-90B, with a disproportionate share flowing into equipment. Contractors such as Rheinmetall report advance payments, fast‑tracked parliamentary approvals and flexible contracting to support rapid capacity expansion, particularly in ammunition and air defense. Budgeted procurement and maintenance spending is now set to rise from roughly €32B in 2024 to around €100B by 2029, while large orders requiring parliamentary approval more than quadrupled from about €20B in 2020 to roughly €80B by 2025.

Capital allocation reinforces these dynamics. For two decades, Europe’s major defense contractors optimised for stable margins, predictable returns and low political risk. They returned capital, avoided aggressive acquisitions and treated excess capacity as waste. And now, even as governments speak openly about urgency, European primes continued to prioritise dividends and buybacks to the tune of $5B in 2025, a problem we wrote about on Air Street Press two years ago. At a time when we need to boost R&D and turbocharge the innovation economy to fight a rapidly evolving war, this is behavior we cannot collectively afford to incentivize.

To make matters worse, ESG-driven investment frameworks has treated defense exposure as reputational risk rather than strategic necessity. The contradiction has become explicit. In Norway, parliamentarians have criticised rules barring the sovereign wealth fund from investing in defense contractors such as Lockheed Martin even as the state buys 52 F-35 fighter jets from the same supplier. Similar tensions now run through Europe’s financial system as banks and asset managers struggle to align stale ESG policies with governments’ rearmament priorities, reinforcing a bias toward stability and incrementalism at odds with the need for scale and sustained production.

What delivery now means

Europe does not need additional strategies. It needs evidence of output.

That means factories running at capacity, missile and interceptor lines sized for replenishment rather than scarcity, contracts long enough to justify expansion, and procurement systems that tolerate speed and accept risk. It also means forces that can be sustained in high-intensity operations, not merely displayed for deterrence.

In 2025, Europe announced seriousness, and in 2026, that seriousness has to show up in production. The continent is capable of doing so because it doesn’t lack the money, talent or motivation. It lacks time. And it cannot complain that its defense industry lacks dynamism while rewarding it for behaving like a bond - safe, predictable and slow.

See you at the Munich Security Conference next month. 🫡

Bonus: come join the Air Street Munich AI meetup on Tuesday 17th Feb 2026 and the Air Street Zurich AI meetup on Thursday 19th Feb 2026!

Key takeaways

This essay assesses the state of Europe’s defense industry in 2025 and the execution risks heading into 2026.

Europe has crossed the political threshold on defense spending, but not the industrial one.

Defense demand is growing several times faster than production capacity.

Germany’s acceleration in 2025 relied on exceptional measures rather than systemic reform.

Capital allocation and procurement incentives still favor stability over surge.

2026 will test whether Europe can translate spending into sustained output.

This gets most of the diagnosis right but it misses the real constraint. Europe’s problem is not that it has forgotten how to produce weapons at scale per se. It is that governments still haven’t made demand credible enough for firms to take irreversible risk.

Defense companies aren’t slow because they’re complacent. They are slow because short contracts, political reversibility and uncertain volumes especially, make large capex irrational. In that context, buybacks aren’t a moral failure, they are just a rational signal that boards don’t believe today’s urgency will survive the next election cycle.

Germany shows this clearly. Output only moved when the state prepaid, guaranteed volumes with accelerated approvals.

Europe doesn’t need more speeches or strategies. All it needs are long-dated and volume-guaranteed contracts. Until then, demand will keep outrunning supply by design.