Introduction

One of the most common questions we’re asked is whether AI is just ‘a bubble’.

Technology commentator Luciano Floridi has described AI as undergoing a hype cycle comparable to the dotcom bubble or the cryptocurrency boom. These claims have been backed up by finance commentators, while Sequoia’s writing around GPU infrastructure explicitly refers to “the AI bubble”.

It’s possible to see the appeal of these kinds of analogies. History is littered with examples of speculative bubbles that left useful infrastructure in their wake. Railway mania in 19th century Britain was bad for retail investors, but pretty good at connecting up cities. Similarly, the dotcom bubble burned investors, but led to telcos overbuilding fiber optic cables, which drove down broadband prices.

Over at Air Street Press, we’re not averse to some gentle skepticism, whether it's shining a light on shaky business models or technical claims that don’t stack up. That said, writing the annual State of AI Report provides a healthy injection of optimism. At 212 slides, this was the longest version of the report ever - simply because there was so much progress that we could have covered. Before edits and trimming, it stood at 250.

Far from showing that AI investment is a speculative bet on a future capability, this year’s report demonstrates the very real value that’s being demonstrated in both the research and commercial worlds.

A bubble that fundamentally changes scientific research

One of the classic mistakes AI skeptics make is to focus on the frothiest corners of the private market, while simply ignoring research progress. In any industry, it’s easy to find charlatans, bad faith actors, or ill-conceived business ideas. Mocking these is easier than engaging with the substance of the work that’s coming out of corporate and academic research labs.

Perhaps the biggest validation yet for AI research came in the days before we published this year’s report, with the news that a number of big-hitters in the world of fundamental AI research had won Nobel Prizes.

AlphaFold, Demis Hassabis and John Jumper’s defining contribution, has shown that it’s not just a one-trick pony. The team has expanded it from the already challenging task of predicting protein folds, to covering their interactions with other biomolecules.

While Google DeepMind’s headline results are impressive, a real cause for optimism is the broadening of the AI research base. When AlphaFold 2 stunned the protein folding community in 2020, the idea that teams would be able to replicate it within a matter of months was unthinkable. But with AlphaFold 3, teams, often with drastically smaller budgets, have been able to produce convincing implementations within months.

This ‘bubble’ technology is also able to bring the R&D costs for novel CRISPR therapeutics tumbling down. These have the potential to unlock a new generation of medical treatments that were previously prohibitively expensive due to a complex web of patents.

AI isn’t just demonstrating its value in solving theoretical challenges, though. It’s showing an ability to fix real bottlenecks in medical workflows, which we exemplify below using synthetic data generation for medical imaging.

Evaluations of these medical AI systems suggests that they’ll be able to significantly improve patients’ interactions with clinicians.

These are only a handful of the research breakthroughs we cite for 2024. If you read the report, you’ll also discover how AI is uncovering novel inorganic materials, deepening our understanding of the brain, and improving atmospheric forecasting.

A bubble with billions in revenue, trillions in value, and widespread enterprise adoption

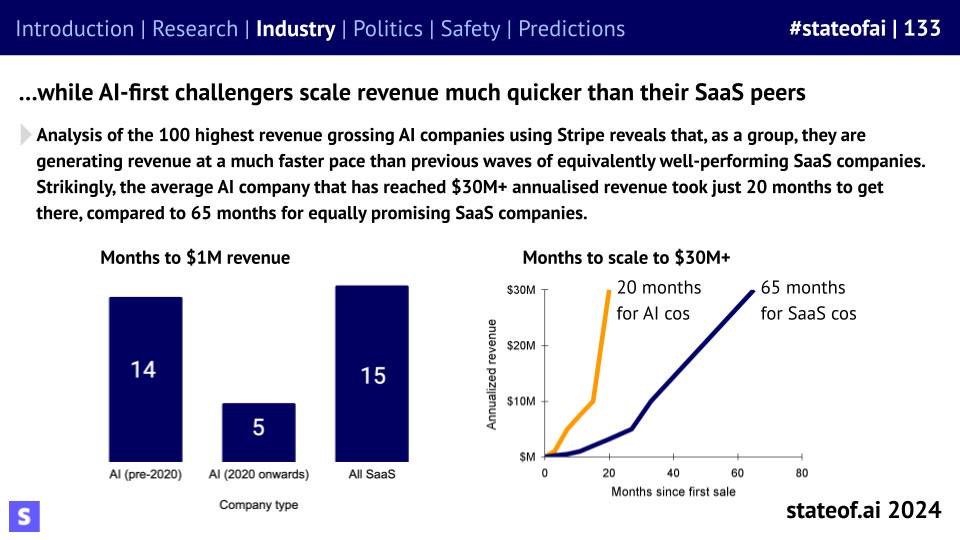

In last year’s report, we looked at some of the challenges AI companies were facing in generating revenue and achieving user stickiness. AI-powered SaaS is no longer having this challenge, with Stripe data suggesting these companies are able to scale to $30M ARR in less than a third of a time of their non-AI peers.

Meanwhile, the model builders are seeing revenue grow steeply, despite competition from big tech and open source. OpenAI is set to rake in $3.7B in revenue this year versus $28M in 2022.

Past ‘bubble’ technologies had little revenue to speak of and limited means of achieving it. They were not being used by 62% of the Fortune 500, like ElevenLabs is, or seeing Synthesia-like exponential user growth.

That doesn’t mean we believe in every new industry or subdomain. Humanoids seem to have a less than ideal form factor for many of their commonly-cited use cases, require significant compute to train, struggle with data bottlenecks and require advanced hardware and likely teleoperations.

But even if every humanoid start-up goes to zero, wiping out around $1B in investment, it will have essentially no wider impact on the market - simply because it’s now so large.

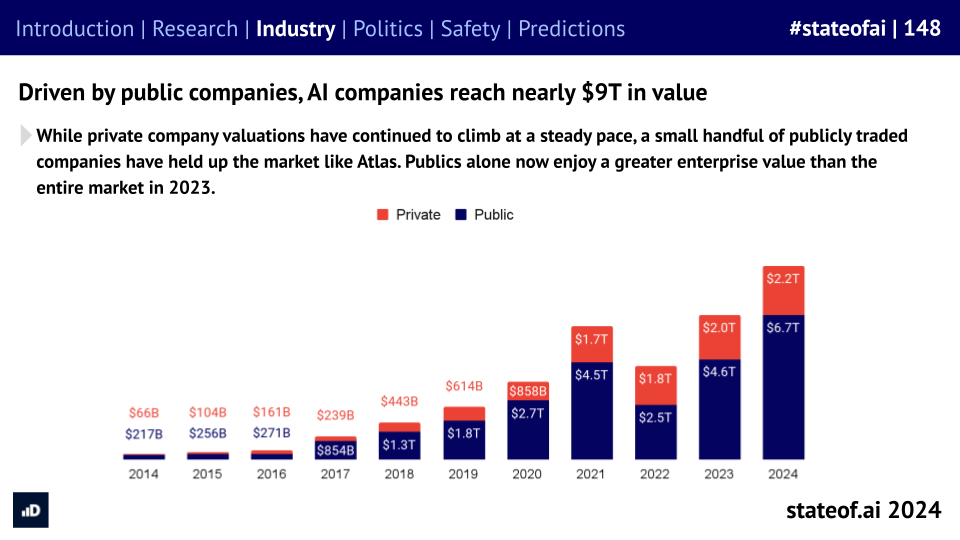

One of the primary characteristics of bubble technologies is the brittleness of their valuations. Even during the interest rate-hike tech slump of 2022, private AI companies grew in value healthily - suggesting a degree of resilience. This stands in contrast to the swift collapse of dotcom companies in the face of recession, or the heart-rate monitor charts that characterize crypto-land.

A bubble that has governments, academics, and industry rushing to build in resilience

One way of measuring a technology’s impact is judging how seriously those with power take it. In the early years of the report, AI was a peripheral issue for governments. While it was seen as an area of competition with China, governments were much more fired up about cheap Chinese steel flooding the markets. Questions like AI safety were much more likely to be discussed on internet forums than in the Pentagon (or even most research labs).

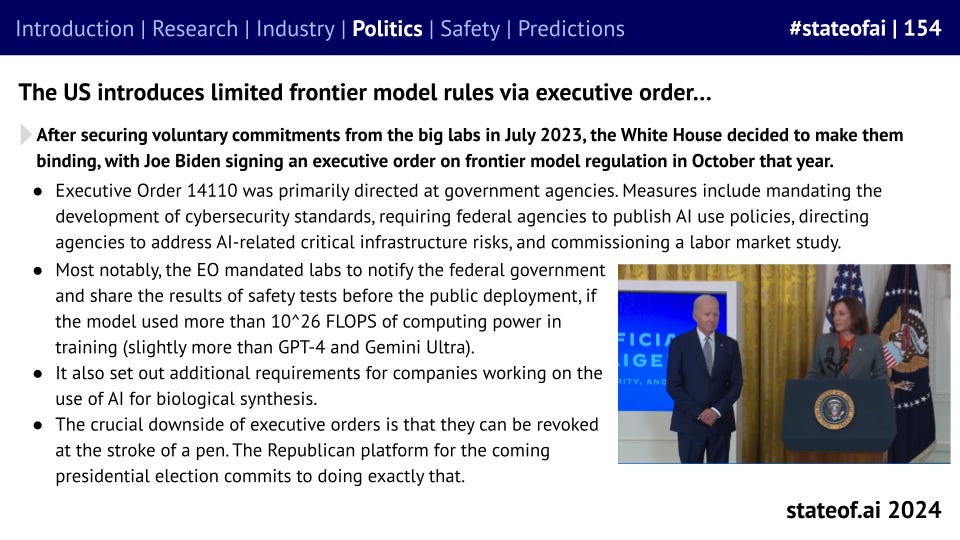

Well, we now have the White House concerning itself with frontier LLM oversight:

Meanwhile, the UK government has fired the global starting gun on AI safety institutes, which bring experts from academia and the private sector into government. After a shaky start, the major frontier labs, with the exception of xAI, have agreed to allow either the UK or US institutes engage in pre-deployment testing of their most powerful models.

On issues like biorisk, we’re seeing leading labs and practitioners agree to set standards on the access management, lab protocols, and the use of specialist tools.

It’s theoretically possible that government, industry, and academia could be investing significant resources in a society-wide resilience effort, against a gloomy fiscal backdrop, for a passing fad. But it’s unlikely. There was no equivalent of this work during the dotcom bubble, while government engagement with crypto has primarily been focused on arresting people for fraud and money-laundering.

When you see this degree of interest and agreement across a range of uncorrelated actors, it’s usually worth sitting up and paying attention.

What a real bubble looks like

While the skeptics like to underestimate AI, we feel they also have forgotten just how wild the dotcom era was. We pass on many companies, because we aren’t excited or don’t feel the founding setup is right, but no one has pitched us on a digital wedding invite business that spent more than twice its revenue on Super Bowl ads. Even the companies with multibillion dollar valuations that we’re unconvinced by typically have built something that’s new or plausibly useful to a group of people.

The dotcom era may have fused hot technology and lack of certainty about future business models, with FOMO, but there are crucial differences. For a start, the dotcom was predominantly a retail phenomenon. In March 2000, the median holding of institutions in internet stocks was approximately 26% versus 40% for non-internet stocks.

As our report shows, AI companies have not been rushing to the public markets over the past couple of years.

This is partly due to post-Covid stimulus choppiness and the interest rate climate of the past couple of years that made private financing more appealing, but it’s mainly because they haven’t needed to.

Deep-pocketed private investors are happy to invest greater and greater sums of money into these companies, while sovereign wealth has emerged as a serious player. Even if frontier labs take a while to sort out their business model or economics, the chances of an OpenAI or Anthropic being unable to pay the bills anytime soon are essentially zero.

Unlike the dotcom companies, who rocketed during a low interest rate-fuelled boom, a significant portion of recent AI investment has occurred against an unfavorable macro backdrop.

The dotcom companies were much closer to the 2021-era SPACs - half-interesting, uncommercial science projects that went public, with the help of cynical institutions (and podcasters) who had no real skin in the game. They did this because retail hype, fuelled by stimulus cheques and lockdown boredom, would give them a better deal than any professional investor.

The other difference is that even AI companies that aren’t likely to succeed long-term have an off-ramp in the form of the pseudo-acquisition. This allows the team’s skills to be redirected to productive ends, while investors get at least a meaningful proportion of their original money back, or in the case of Character.AI, a premium.

These are hardly the 99% discounted firesales of the dotcom era, where companies that had little of value beyond secondhand PCs and ergonomic chairs were scooped up as the market cratered.

Perhaps the closest parallel we can see with the dotcom bubble is Sequoia’s argument about overbuilt GPU capacity. Putting aside some of our questions around the math (we’re not sure where the 50% build and cost to operate number comes from), it’s a thoughtful argument that suggests the value of hardware is set to plummet. During the dotcom bubble, high-speed internet infrastructure was overbuilt for a wave of companies that then went bust. Telcos lost a fortune as they slashed prices, creating affordable broadband for consumers. The infrastructure was overbuilt, but it was eventually used.

We’re beginning to see this dynamic play out in AI. Multiple resale markets are now pricing H100 time at under $2/hour, down from $8 last year. That said, AI companies being able to access a crucial resource at a more affordable price doesn’t strike us as a crisis. It’s bad news for newer resale marketplaces that lacked the foresight to lock companies into multi-year commitments. Resellers who endured the 2018 crypto GPU boom and bust had already learnt their lesson.

Closing thoughts

There’s almost something quaint for us in discussions about AI bubbles. It reminds us slightly of the 2017-18 era, where any sign that AI venture investment was slowing was over-interpreted as proof that an ‘AI winter’ was about to hit. By now, AI has spread across so many different industries, areas of research, and companies that it’s difficult to envisage what kind of shock could bring it all crashing down.

There will, of course, be high profile failures, downrounds, and doomerism. But it’s easy to forget that this is just business as usual for markets. The majority of venture-backed companies are not successful and that holds true across every sector.

This year’s report left us more optimistic than ever going into 2025 and we hope it does the same for you.

Broadly on the same page. Somewhat worryingly, this could’ve been otherwise titled: ‘This time actually is different’