Prefer narration? Listen to the audio version of this post.

Introduction

It’s been close to six months since we published our report covering the challenges early-stage defense companies face in Europe. Since then, we’ve seen a rush of defense-related announcements from European governments, speculation about the future of US support for the Ukrainian war effort, and the Russian military continuing to step up its offensive.

Given the pace of developments, we’re re-examining our initial work and assessing what’s changed, what hasn’t, some points we didn’t evaluate last time, and where we go from here.

The innovation arms race

The war in Ukraine underscores the importance of both acting urgently and focusing on the right challenge. Our previous report correctly touched on Ukrainian innovation, which has been widely documented in media coverage. Unsurprisingly, however, innovation in this conflict has not been one-sided.

While initially caught off-guard, the Russian military has quickly sought to learn from Ukrainian tactics and weaponise them. Both sides have demonstrated considerable agility in copying from each other throughout this conflict.

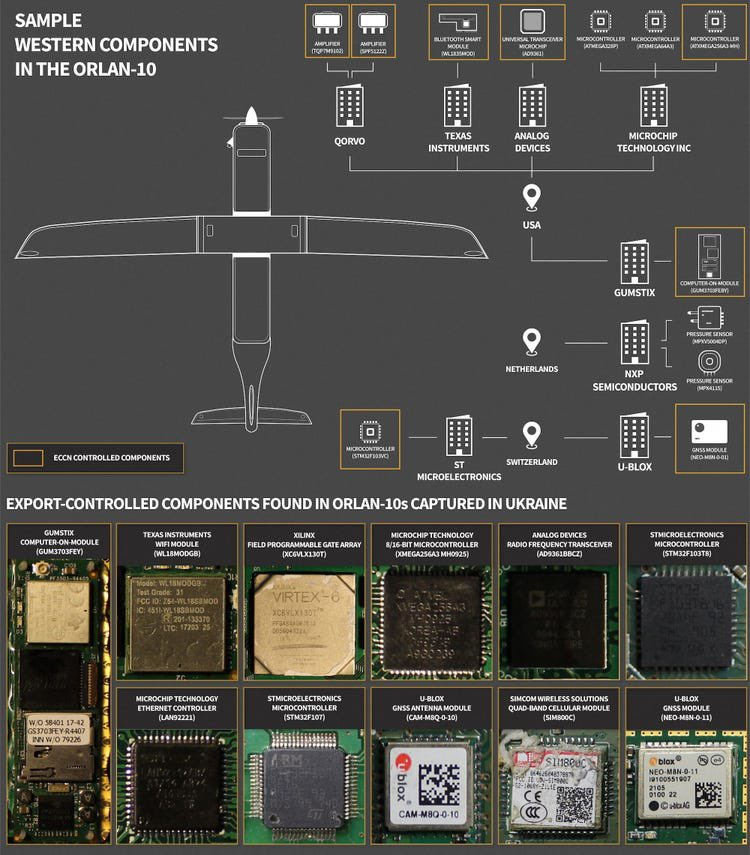

Fighting takes place under a drone-infested sky, with 90% of injuries in some areas stemming from FPV drones and drone-dropped munitions. These range from more expensive Shahed drones, imported from Iran or assembled domestically, or the less sophisticated Orlan-10, which is used for reconnaissance. The Orlan, despite being critiqued for its often crude assembly, has played a vital role in helping find targets, collect intelligence, and support Russian electronic warfare. Crucially, it is also cheaper and easier to produce than it is to shoot down. It’s also helpfully powered by a series of western components:

Meanwhile, the vast majority of drone-dropped munitions that don’t rely on improvised volunteer drones use off-the-shelf DJI drones from China.

These efforts have been supplemented by an array of volunteer efforts that are reminiscent of some of those seen on the Ukrainian side.

It is difficult to verify the prevalence and effectiveness of many of these volunteer efforts, as much of the source material comes from pro-Russian Telegram accounts. However, we do know that they are receiving government support and there is no shortage of publicly available video of their drones apparently being deployed to the frontline.

A Russian studio has also created a pirated version of a powerful FPV simulation game, which had originally been created by a Finnish company to support the Ukrainian war effort. A contact of ours, close to UK drone efforts, has warned us that is eerily realistic and competitive with Ukrainian equivalents. While available openly via Steam, we wouldn’t recommend downloading, as we don’t know what spyware may be lurking within.

While we definitely saw a mini-exodus of Russian tech talent in 2022, obituaries for the industry now seem premature. There are reports that large numbers of people with valuable tech skills have in fact returned to the country, lured by the promise of generous payouts from the government. It’s also clear that in any future conflict, it is unlikely that we will be able to rely on a sanctions regime to cut off access to advanced technology. As well as European components semi-regularly turning up inside Russian drones, Russian middlemen aren’t struggling to get hold of Starlink terminals.

The other concerning development has been the failure of many western innovators to make a significant difference on the front-line. The clearest case of this are the challenges US drone manufacturers have run into when faced with Russian electronic warfare. So far, this has proven able to adapt quicker than equipment manufacturers can roll out updates. This technology has also been used to inflict chaos on Estonian airspace and even grounded the UK defense secretary’s plane, which was missing crucial defenses due to budget cuts.

Peacetime versus wartime mindset

Given the clear importance of both a strong industrial base, flexibility, and affordable mass, we should be expecting to see a gear-shift in Europe.

In our original report, we highlighted the ‘peacetime’ vs ‘wartime’ split in the European psyche, predominantly along geographical lines. This meant that Eastern European countries have largely been increasing defense spending rapidly, rearming, and pushing for more substantial aid to Ukraine. Meanwhile, further west, things have been proceeding at a comparatively lethargic pace.

Readiness in the Eastern European and Baltic countries remains a priority, even during challenging economic conditions. Not only are these countries continuing to increase defense spending as a proportion of GDP, we’ve seen:

Estonia announce a €50M defense technology fund, with the potential to grow larger, which crucially, will not focus on dual use;

Lithuania cut the time required for defense manufacturers to set up operations in the country from 2 years to 6 months by streamlining approvals and has introduced generous tax incentives;

Poland increased its purchase of off-the-shelf UAVs, while the country is gearing up to launch its first military satellites next year.

Moving further west, the picture is more mixed. While investment levels are definitely increasing, there are lingering questions about strategy, readiness, and procurement methods.

France has certainly shifted tonally, with President Macron’s surprising suggestion that French troops could be deployed to Ukraine. We’ve also seen France increase spending on military R&D, pledging €300M a year on an agency dedicated to military applications of AI. Government-back technology investment in France, however, is not famed for its speed, effectiveness, or flexibility. It’s crucial that any body doesn’t simply subsidize long-standing incumbents and that there’s a clear roadmap for bringing the product of this R&D to the frontline at scale.

We see some of these typical patterns in French policy reasserting themselves in their approach to defense M&A exits. The government appears to be restricting these to acquisition by a very small pool of French corporations, making it difficult to see how the sector will be venture-backable. This is concerning, given how uncertain the exit market already looks for defense technology.

In Western Europe the lack of readiness extends beyond procurement. There have been a string of embarrassing incidents, ranging from China hacking the UK Ministry of Defence through to missile misfires and revelations about the woeful state of German military communications, which suggest that readiness remains in a poor place. Meanwhile, the drip feed of revelations about former Wirecard COO and Russian agent Jan Marsalek’s thorough penetration of the Austrian government should concern us all.

The UK: revisiting our central case study

Our report took the UK as its primary case study, finding a combination of hazy strategy, underfunding, and botched execution.

Perhaps the most significant single move was the government’s announcement that defense spending would increase from 2.2% of GDP to 2.5% by 2030. This was extravagantly branded as a ‘turning point’ for European security. While additional funding is always welcome, reaction in the UK was mixed. The government announced its intention to find the additional money through unspecified civil service job cuts. Similarly, the claim that this would total £75B in extra funding was quickly shown to be a 3x exaggeration, produced by disingenuous benchmarking.

The other significant bright spot has been the news that the AUKUS nations are preparing to exempt each other from their defense export control regimes. Not only does this open up major new export markets for innovators, it makes partnership and the sharing of classified information significantly easier. It also makes the UK the most logical country in Europe by far to incorporate a defense start-up. Our friends at Lambda Automata building a significant London presence being a case in point.

Beyond that, there have been a few interesting acquisition developments.

The new Challenger 3 tank is entering final production under an £800M contract with Rheinmetall BAE Systems Land. 148 of these will become the Army’s Main Battle Tank, remaining in service until 2040. This suggests it’s business as usual at the Ministry of Defence.

While the initial delivery of the Challenger 2 was announced with great fanfare, it’s been far from a game-changer in Ukraine. Traditional platforms that take years to build and which are specified down to the last bolt are difficult to adapt in the face of field conditions. That’s why only half of those sent to Ukraine are in operation, due to reliability and maintenance issues, while it takes months for spare parts to arrive. Meanwhile their weight causes them to become regularly stuck in the mud and require towing. Concerningly, the Challenger 3 will be even heavier.

Beyond questionable choices around traditional hardware, the government also published the Defence Drone Strategy in February. The 12 page document (8 of which are the covers, introduction, photos, glossary, and past case studies) lists a £4.6B resource commitment over the next 10 years, but is light on detail. It largely repeats long-standing aspirations around R&D, cooperating closely with industry, simplifying acquisition, and embracing open architectures. While these may be good things, they are not firm, measurable commitments or a plan.

It remains unclear if the UK government will be able to end its dependence on expensive, bespoke platforms in this arena. When it comes to UAVs, this approach has already been a disaster. The UK’s Watchkeeper programme resulted in a £1.5B outlay over several years to deliver 54 drones years late, none of which are on operational deployment. Originally meant to be a copy of the successful Israeli Hermes 450, in classic MOD style, 2,000 systems requirements were added to the programme, making the drones too heavy. It also transpired that they could not handle bad weather. Meanwhile, the RAF’s specialist drone squadron has not conducted a single trial since 2020, due to budget shortfalls. This stands in contrast to the delivery of the Ghost Shark autonomous submarine project by Anduril, which came in on budget and early.

As with France’s R&D agency, it’s worth questioning the extent to which European governments necessarily need to engage in highly capital-intensive R&D projects or multi-year partnerships with industry when so much technology is already available off-the-shelf.

Whether it’s the Defence Drone Strategy, the R&D boosts built into the defense spending uplift, admittedly cool lasers, this expensive domestic innovation drive risks becoming a distraction. When components like drones, optical and thermal cameras, edge computing hardware, and guidance and navigation devices are essentially commoditized, it seems bizarre to approach procuring them like a traditional manned platform. Especially given the clear value that cheap drones, treated as ammunition rather than aircraft, have demonstrated. Fresh R&D spending needs to avoid becoming another round of innovation theater. This will divert attention away from fixing a fundamentally broken acquisition system. Scale and efficiency are much more likely to win out than elegance.

Closing thoughts

While much has happened, it feels that the same reluctance to tackle fundamental challenges persists in many European countries. Symbolically throwing good money after bad may be easy, but it’s wasteful and only creates a smokescreen of reassurance. As we said in our original report, we don’t believe change is likely to be driven by the small group of incumbents whose business model depends on multi-year contracts for bespoke platforms. It’ll be innovators, whether it’s Lambda Automata, the people who recently spent their weekend at a London defense hackathon, and other early-stage innovators.

It’s our belief that good institutional wiring and agility are usually more important than raw investment. The solution here is either root-and-branch reform or hiving procurement out into a separate, well-funded specialist agency exempt from the usual rules. It does not lie in a constellation of new innovation hubs, state-led R&D programmes, or government subsidies for the VC sector. The UK is gearing up to launch a new Defence Innovation Agency in 2025 - this is the perfect opportunity to be radical. Based on current trends, however, we are on course for the missed opportunity of a lifetime.